“End of an Era”: OpenAI’s AGI Readiness Chief Resigns and Team is Disbanded

Miles Brundage was one of the last of the AI safety old guard at OpenAI. He thinks the world is not ready for powerful AI.

OpenAI is disbanding its AGI readiness team — and its Senior Advisor for AGI readiness, Miles Brundage, just resigned after over six years at the organization.

The company defines artificial general intelligence (AGI) as “a highly autonomous system that outperforms humans at most economically valuable work.” And Brundage defines “ready for AGI” as roughly “readiness to safely, securely, and beneficially develop, deploy, and govern increasingly capable AI systems.”

So is OpenAI prepared for the thing it’s explicitly trying to build?

No, according to Brundage.

In an accompanying Substack post, he writes, “In short, neither OpenAI nor any other frontier lab is ready, and the world is also not ready.”

His jarring answer is followed immediately by a less than reassuring clarification:

To be clear, I don’t think this is a controversial statement among OpenAI’s leadership, and notably, that’s a different question from whether the company and the world are on track to be ready at the relevant time (though I think the gaps remaining are substantial enough that I’ll be working on AI policy for the rest of my career).

Buried in Brundage’s announcement tweet is the news that the AGI readiness team is being disbanded and absorbed into other teams.

So what?

Brundage was one of the last of an old guard of AI safety and governance employees of the AI company. His departure is yet another sign that OpenAI, as we knew it, is dead.

“Miles is leaving OpenAI = end of an era,” tweeted Haydn Belfield, a Cambridge existential risk researcher and long-time collaborator of Brundage, whose departure announcement prompted a deluge of well-wishes from AI figures who usually agree on very little.

At a glance, there doesn’t appear to be much bad blood between Brundage and OpenAI. He writes:

I think I'll have more impact as a policy researcher/advocate in the non-profit sector, where I'll have more of an ability to publish freely and more independence. OpenAI has offered to support this work in various ways…

However, it’s hard not to think that the timing of his exit might have something to do with the recent reports that OpenAI is trying to restructure as a for-profit public benefit corporation (PBC) as a condition of keeping the $6.6 billion it just raised in its latest funding round.

For instance, here's what Brundage had to say when OpenAI first spun up its for profit arm in 2019:

When I first heard about OpenAI LP, I was concerned, as OAI's non-profit status was part of what attracted me. But I've since come around about the idea for two reasons:

1. As I dug into the details, I realized many steps had been taken to ensure the org remains mission-centric.

2. It was reassuring that so many others at the org had raised such concerns already, as ultimately this is a matter of culture, and I'm thrilled to work with dozens of colleagues who also care deeply about the impact of AI on the world!

Over five years later, things look very different.

The first major test of the nonprofit board’s power came and went with November’s short-lived firing of CEO Sam Altman.

(Brundage was one of the earliest signatures calling for Altman’s reinstatement, however, over 700 of OpenAI’s 770 employees signed that letter, and I’ve spoken to at least one signatory who changed their mind after more information came to light.)

In response to Altman’s abrupt firing, employees rallied behind the slogan: “OpenAI is nothing without its people.” But nearly a year later, the people that OpenAI is purportedly “nothing without” are mostly different. The company has since grown its headcount by nearly 1,000 employees, to 1,700.

In that same period, OpenAI has lost the majority of its most safety conscious employees. Fortune reported in August that more than half of the employees focused on AGI safety had left the company in just the previous few months.

Additionally, a close read of Brundage’s Substack post hints at some larger frustrations. For example, when explaining why he left, he writes:

To be clear, while I wouldn’t say I’ve always agreed with OpenAI’s stance on publication review, I do think it’s reasonable for there to be some publishing constraints in industry (and I have helped write several iterations of OpenAI’s policies), but for me the constraints have become too much.

In other words, OpenAI was policing his publications too harshly, which shouldn’t come as a surprise when you remember that Altman reportedly tried to fire Helen Toner from the nonprofit board over an obscure academic paper she co-authored that he felt was too critical of OpenAI’s commitment to safety.

Brundage also writes that he’s done much of what he’s set out to do at OpenAI and that he’s “already told executives and the board (the audience of my advice) a fair amount about what I think OpenAI needs to do and what the gaps are.”

Sounds nice enough, right? But as @renormalized tweeted:

I'd be surprised if Miles expects to have nothing new to say on these topics in the future, so if he's finished telling OpenAI execs about what they need to do re: AI policy (especially the need for regulation), the natural conclusion is that he saw they weren't listening.

Brundage is also careful not to single out OpenAI when he complains about corner-cutting on safety — there are plenty of examples of this from rival AI companies — but he also didn’t say that OpenAI was better on this front either.

There are some years where decades happen

Some think automated AI scientists will make decades of discoveries in just years. OpenAI appears to be trying to demonstrate this principle by compressing decades of corporate scandals into a single year.

In May, the company disbanded its Superalignment team, which was tasked with determining how to make superintelligent systems safe in under four years. The two team leads, Ilya Sutskever and Jan Leike, left the company. On his way out the door, Leike publicly criticized OpenAI, tweeting:

Building smarter-than-human machines is an inherently dangerous endeavor. OpenAI is shouldering an enormous responsibility on behalf of all of humanity. But over the past years, safety culture and processes have taken a backseat to shiny products.

Fortune subsequently reported that the Superalignment team never got the 20 percent of compute it was promised.

The day after Leike departed, OpenAI was roiled by the revelation that it required outgoing employees to sign draconian, lifetime non-disparagement and non-disclosure agreements to retain their vested equity, often the vast majority of their total compensation. The practice had been in place since at least 2019 and was only revealed because of Daniel Kokotajlo’s courageous refusal to sign the agreements and his subsequent choice to share details with Kelsey Piper of Vox.

And in a much less reported story, OpenAI removed Aleksander Madry from a senior safety role in July. His safety responsibilities were given to a different team and effectively deprioritized.

Brundage’s farewell

Brundage’s farewell post is long and worth reading in full, but I’ve pulled out some of the most significant bits here.

As previously mentioned, he mainly says that going independent will allow him more freedom and time to work on “issues that cut across the whole AI industry.” He plans to start or join an existing nonprofit focused on AI policy research and advocacy, “since I think AI is unlikely to be as safe and beneficial as possible without a concerted effort to make it so.”

Brundage is careful to emphasize that “OpenAI remains an exciting place for many kinds of work to happen, and I’m excited to see the team continue to ramp up investment in safety culture and processes.”

It’s completely possible that Brundage genuinely has few gripes with OpenAI and remains optimistic about its attitude toward AI safety research.

But here’s a different hypothesis: If you worked at OpenAI on safety and governance and found that you were not getting the resources and prioritization you thought were appropriate, there’s value in telling the rest of the world, as doing so increases pressure on the organization to change its practices and may make regulation more likely. However, this will also predictably dissuade other safety-minded people from joining going forward. If the culture and leadership were immovable on safety policies, then scaring committed people off won’t matter too much — their presence wouldn’t have made a difference.

But if the culture and leadership aren’t immovable, then making it more likely that all the really serious safety people avoid OpenAI going forward could be bad! Especially since there aren’t many regulations on frontier AI systems and that may not change any time soon. If you think AGI could come in a matter of years, as many at OpenAI do, the people in the room at the first place to build it could have a massively outsized impact on how well it goes.

There is some indirect evidence that this was a consideration for Brundage, who writes, “Culture is important at any organization, but it is particularly important in the context of frontier AI since much of the decision-making is not determined by regulation, but rather up to the people at the company.”

He also calls on Congress to:

robustly fund the US AI Safety Institute, so that the government has more capacity to think clearly about AI policy, as well as the Bureau of Industry and Security, so that someone in the government will have some idea of what happens to advanced AI chips after they are exported.

Brundage expresses concern about “misalignment between private and societal interests, which regulation can help reduce,” and corner-cutting that can happen without deliberate efforts.

Despite a long record of rhetorically supporting regulation, OpenAI formally opposed the first major binding AI safety bill in the US, California’s SB 1047, which was vetoed by governor Gavin Newsom on September 29th. You can check out my extensive coverage of the epic fight over the bill here.

A call for cooperation with China

Perhaps the most significant part of Brundage’s post is his dissent from the growing chorus of powerful voices (including Sam Altman) pushing for an AI arms race against China:

While some think that the right approach to the global AI situation is for democratic countries to race against autocratic countries, I think that having and fostering such a zero-sum mentality increases the likelihood of corner-cutting on safety and security, an attack on Taiwan (given its central role in the AI chip supply chain), and other very bad outcomes. I would like to see academics, companies, civil society, and policymakers work collaboratively to find a way to demonstrate that Western AI development is not seen as a threat to other countries’ safety or regime stability, so that we can work across borders to solve the very thorny safety and security challenges ahead.

And even though he thinks the West will continue to outcompete China on AI, Brundage writes that autocratic countries have:

more than enough ‘gas in the tank’ of computing hardware and algorithmic progress… to build very sophisticated capabilities, so cooperation will be essential. I realize many people think this sounds naive but I think those people haven’t thought through the situation fully or considered how frequently international cooperation (enabled by foresight, dialogue, and innovation) has been essential to managing catastrophic risks.

I think the next major fault line in the AI debates will be posture toward China. Altman, Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei, and former OpenAI researcher Leopold Aschenbrenner have prominently advanced varieties of the idea that democracies must ‘prevail’ over China in a race to build superhuman AI systems.

Others, like Brundage, prefer a cooperative approach to China.

Existential clash of civilizations thinking motivated the most dangerous choices ever made, from the nuclear arms buildup to the Soviets’ illegal, secret bioweapons program. The mere belief in this narrative with respect to AGI could motivate profoundly destabilizing actions, like a nuclear first-strike.

We can and should instead approach the challenge of safely building AGI as one of global, rather than national security.

I’ll have a lot more to say on this topic soon.

For now, I’ll just say that we should be very wary of letting science guys with toy models of the world dictate international relations. And we should think harder about how China is likely to react if the “free world” moves mountains to kneecap their AI progress.

I’m also looking forward to seeing what Brundage writes next, unencumbered by corporate overseers.

Appendix:

Where did the co-authors go?

I checked out four of the papers Brundage co-authored in 2019 and 2020. Of the 29 authors at OpenAI at the time of publication, only five were still there (there may be some overlap).

Five years is an eternity in startup world, so this doesn’t mean a ton on its own. However, the ways in which these folks left are, shall we say, atypical.

For example, this February 2019 paper on the policy implications of GPT-2 names these authors: Alec Radford, Jeffrey Wu, Dario Amodei, Daniella Amodei, Jack Clark, Miles Brundage, and Ilya Sutskever.

Dario and Daniela Amodei started Anthropic with Jack Clark and other OpenAI defectors after reportedly trying to push Altman out over safety concerns in 2021 (Anthropic officially disputes this account).

Sutskever voted to fire Altman in November 2023, caved under immense pressure and reversed his decision. He never returned to the office and formally left OpenAI in May to launch Safe Super Intelligence.

Alec Radford and Jeffrey Wu were the lead authors on the GPT-2 technical paper.

Wu left in July and said this to Vox in September following reports that OpenAI was planning to transform from a nonprofit to a for-profit:

“We can say goodbye to the original version of OpenAI that wanted to be unconstrained by financial obligations.”

“It seems to me the original nonprofit has been disempowered and had its mission reinterpreted to be fully aligned with profit.”

“The general public and regulators should be aware that by default, AI companies will be incentivized to disregard some of the costs and risks of AI deployment — and there’s a chance those risks will be enormous.”

Radford is the only author from both GPT-2 papers still at OpenAI.

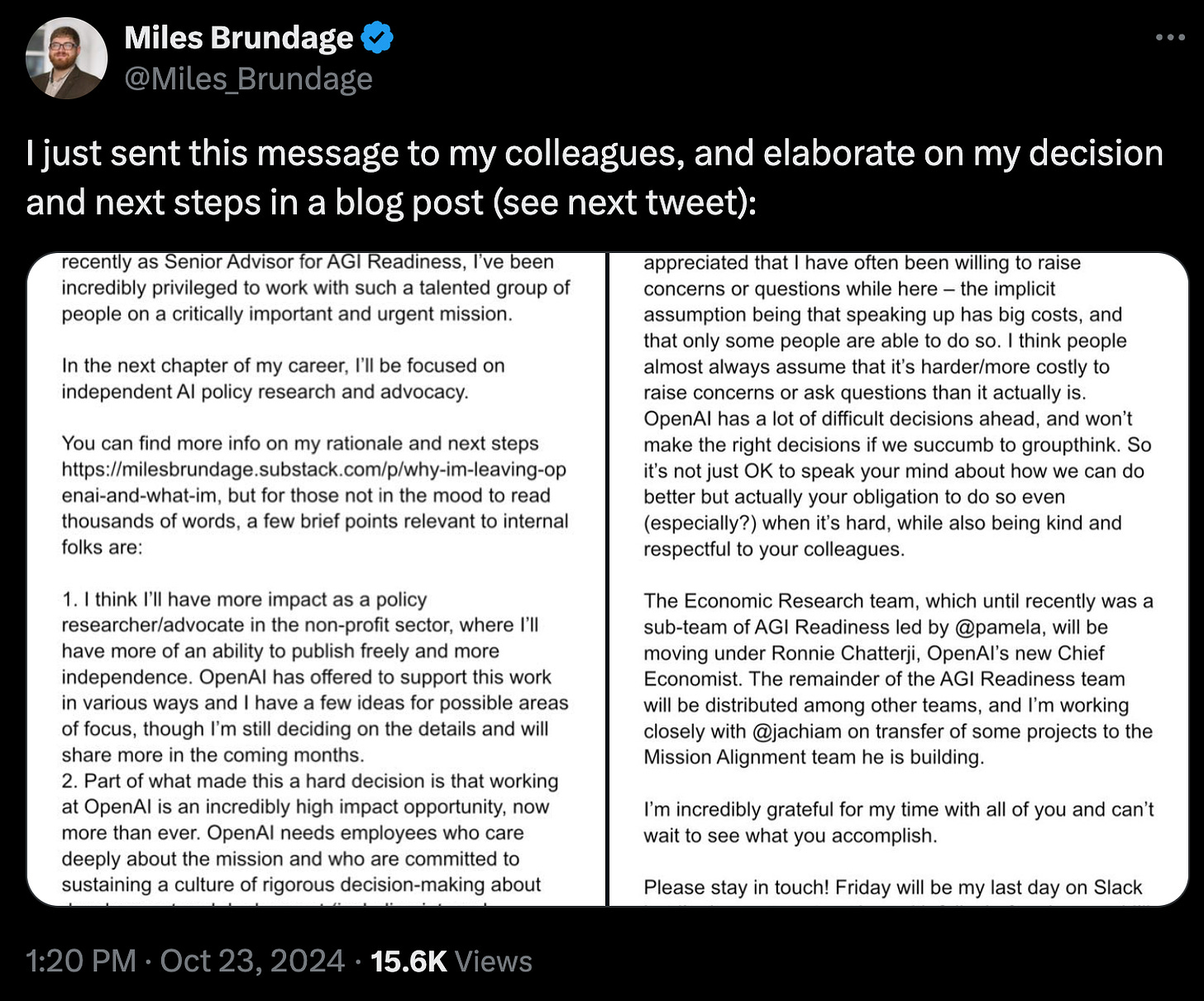

Full announcement text

I asked Claude to transcribe Brundage’s full announcement message from the screenshots he posted:

Dear all,

I recently made a very difficult decision to leave OpenAI. In my six years here, first as a Research Scientist on the Policy team, then as Head of Policy Research, and most recently as Senior Advisor for AGI Readiness, I've been incredibly privileged to work with such a talented group of people on a critically important and urgent mission.

In the next chapter of my career, I'll be focused on independent AI policy research and advocacy.

You can find more info on my rationale and next steps https://milesbrundage.substack.com/p/why-im-leaving-openai-and-what-im, but for those not in the mood to read thousands of words, a few brief points relevant to internal folks are:

1. I think I'll have more impact as a policy researcher/advocate in the non-profit sector, where I'll have more of an ability to publish freely and more independence. OpenAI has offered to support this work in various ways and I have a few ideas for possible areas of focus, though I'm still deciding on the details and will share more in the coming months.

2. Part of what made this a hard decision is that working at OpenAI is an incredibly high impact opportunity, now more than ever. OpenAI needs employees who care deeply about the mission and who are committed to sustaining a culture of rigorous decision-making about development and deployment (including internal deployment, which will become increasingly important over time). The precedents we set with each decision and launch matter a lot. We only have so much time to uplevel our culture and processes in order to effectively steward the incredibly powerful AI capabilities to come.

3. Remember that all of your voices matter. Some people have said to me that they are sad that I'm leaving and appreciated that I have often been willing to raise concerns or questions while here – the implicit assumption being that speaking up has big costs, and that only some people are able to do so. I think people almost always assume that it's harder/more costly to raise concerns or ask questions than it actually is. OpenAI has a lot of difficult decisions ahead, and won't make the right decisions if we succumb to groupthink. So it's not just OK to speak your mind about how we can do better but actually your obligation to do so even (especially?) when it's hard, while also being kind and respectful to your colleagues.

The Economic Research team, which until recently was a sub-team of AGI Readiness led by @pamela, will be moving under Ronnie Chatterji, OpenAI's new Chief Economist. The remainder of the AGI Readiness team will be distributed among other teams, and I'm working closely with @jachiam on transfer of some projects to the Mission Alignment team he is building.

I'm incredibly grateful for my time with all of you and can't wait to see what you accomplish.

Please stay in touch! Friday will be my last day on Slack but I'm happy to set up time with folks before I go, and I'll still be in the Bay.

What I see here is similar to what my co-author and I discovered when we wrote our well-received account of the Deepwater Horizon disaster. In the late 1990s the head of BP, to the applause of McKinsey and Stanford Business School (two institutions that should never be let near a high-consequence engineering project) made BP the most efficient producer of oil in the Gulf of Mexico. He did this by stripping all of the redundancy out of the organization. All that was left were forward-looking, "get 'er done, son" elements and there was nobody left who could say "no" or even alert upper management to potential for disaster. And disasters followed: two million barrels of oil spilled on the Alaska tundra, 15 dead in the Texas City refinery explosion, and 11 dead and the largest man-made ecological disaster in the history of the U.S. when the Macondo well blew out.

I see OpenAI reconfiguring itself in the same way, applauded by the same finance-first culture for the same reasons, and running the risk of the same kind of multiple catastrophe. Fasten your seat belts, folks, it's going to be a bumpy ride.

“OpenAI, as we knew it, is dead.”

I'll suggest instead that OpenAI, as we thought we knew it, was never alive. It was a dream. The dream, shared by employees, investors, and the public, was that software more capable than existing search engines, conversational agents, and generative tools would quickly find sufficient revenue streams to support an ongoing commitment to focus on safe and secure accomplishment rather than on profitability. Those revenue streams have not materialized, the dream dematerialized, and here we are, with no need to assume bad intentions anywhere.